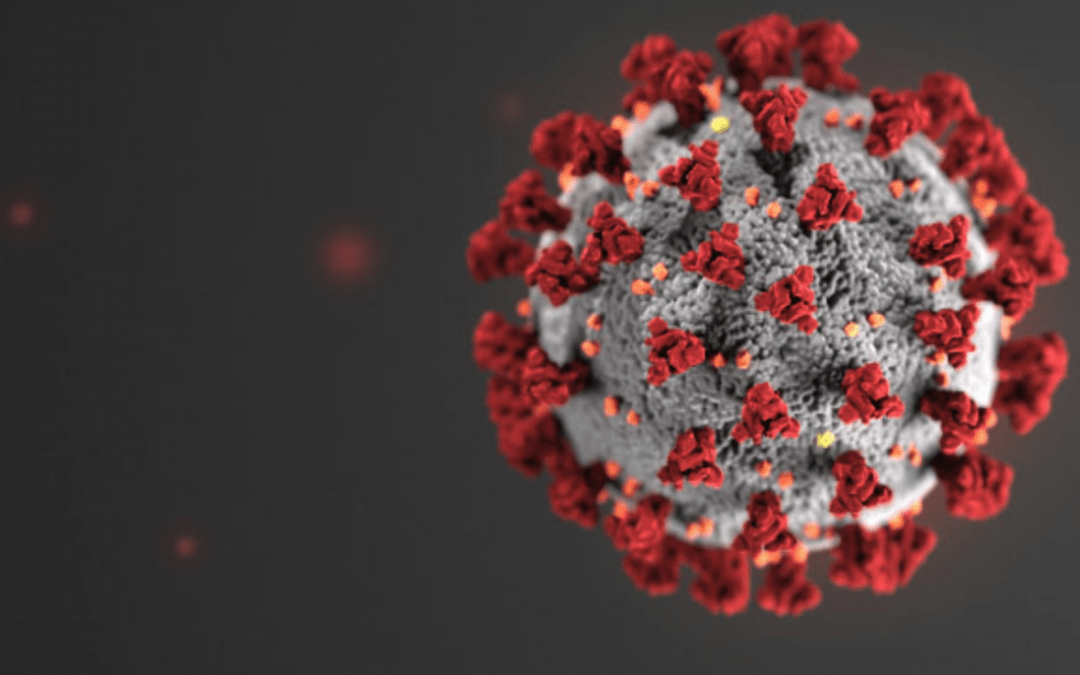

Photo courtesy of cdc.gov

INTRODUCTION

Students in Professor Raymond McCaffrey’s Spring 2020 Ethics in Journalism class at the University of Arkansas met for the last time together in Kimpel Hall on March 12. As they followed instructions about plans to cease face-to-face meetings and go to online instruction, the students received an email from university officials officially announcing the move to remote learning.

In the weeks since then, the more than 30 students have spread out from one coast of the country to the other, from Maryland to California, some of them staying around Fayetteville while others have moved to be with friends, family and loved ones throughout Arkansas and in places such as Memphis, Dallas, Kansas City, and Norman. As they have felt the course of their lives change – one student has already had a parent laid off from work – they have managed to continue to study journalism ethics and its importance in a democratic society at a time of crisis.

Virtual Lecture from Professor McCaffrey: March 31, 2020

The larger topic today concerns the value of information in the age of the coronavirus. (Obviously, your poll question relates to this topic.) Is there too much information out there about the virus or not enough? Is the information out there reliable?

My larger goal with our class is that every student walks away with a better understanding of how journalism works or should work, since that should help you manage your personal news diet. The word “diet” can seem off-putting, since it seems to suggest a scolding might be in the works: Eat your vegetables and cut out desserts. I’m thinking about something else. In ordinary times, we should have a balanced news diet mixed with a variety of sources that are good for you, plus some that are just entertaining. I would also add that anytime there is a news story of considerable magnitude, it’s probably good to guard against unnecessary binging. The Poynter Institute offers a guide that might be of interest.

The stories unfolding are tragic and heartbreaking, but they can also be inspiring: tales of nurses and doctors bravely attempting to save lives on the front lines, researchers racing against the clock to produce a cure; others working to develop crucial medical tests and equipment. Journalists are telling those stories in an impressive fashion, taking advantage of latest digital storytelling tools.

Here’s a New York Times story about what researchers are doing to find a cure.

The New Yorker takes a look at the grass-roots effort to manufacture ventilators to treat those suffering from the virus. (Ingenuity has always been the most potent weapon in the war against sickness and disease.)

The story of how the virus is affecting the daily lives of ordinary Americans is important as well. Here’s another New Yorker story that should be of interest to all of you: how the virus has affected college students in the U.S.

A deeper read of some of these stories will reveal issues that directly relate to journalism ethics. We have talked about balancing the first two important principles of the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics: the need to “Seek Truth and Report It” while also taking care to “Minimize Harm.” (Our recent discussion of ethical concerns about respecting privacy brought us to the case of Arthur Ashe, the late champion tennis player who revealed that he had contracted the AIDs virus from a blood transfusion, but only after a newspaper threated to do a story about it. Would publishing such an important story appropriately minimize the harm done to the subject?)

This story from the Poynter Institute touches upon the ethical concerns in identifying those who are being treated for COVID-19.

This New York Times story talks about how public health officials are wrestling with the decision to release certain information about the virus. (For journalists, this potentially leads to a dilemma like we saw with the Pentagon Papers case: When should journalists publish information they feel the public ought to know even though government officials say it should not be released?)

More and more, journalists are taking it upon themselves to actively identify misinformation. Here’s a tip sheet from Poynter about how not to be fooled about the coronavirus.

There are an array of impressive digital maps created to elucidate the spread of the coronavirus. Agencies such as the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Protection, and state health departments can be useful sources for raw data. But the best journalists are going beyond this. Read about the COVID Tracking Project.

This New York Times story is about an online map tracking the incidence of fevers in the U.S. The map is the work of a company that makes thermometers. Right away, that revelation should serve as a red flag as to a possible conflict of interest. The Times story is transparent about that. But for those of you pursuing a career in public relations, this might serve as evidence of the kind of work you can do, (particularly if you overcame your aversion to math and took a data journalism class offered by the School of Journalism and Strategic Media.) Read this carefully, so you know what the map is and isn’t . It isn’t tracking the virus. It’s tracking an indice of fevers experienced by people in certain geographic regions. Why should we care about the incidence of all fevers, even those unrelated to the virus? That might give us a clue as to how well the practice of social distancing might be working in a given area. (Plug in your zip code and you will see what is happening where you live.)

Here’s a poll by the Pew Research Center about how one’s news diet may affect the knowledge about the pandemic.

Here’s another poll by the Pew Research Center about how participants rate the media’s performance during the crisis.

Finally, there are news stories that offer important information; then there’s great writing that offers something more. Two magazines that have historically offered excellent long-form journalism are continuing to do so in the digital world. If you want to take the time to really know what’s going on with the coronavirus, I offer two excellent in-depth stories.

Here’s one from the Atlantic, which looks forward at the future of the fight against the virus.

A second one from the New Yorker looks to the past for some answers.